It was the redness of the earth below that impressed me most as the plane descended into Alice Springs. Now I saw vividly why this part of Australia’s Northern Territory is called the “Red Centre”. This is a vast terrain of dusty scrubland and deserts across the middle of this island continent. And right in the centre of that is Alice Springs, mid way between Darwin to the north and Adelaide to the south, with both cities some 1,500 miles away.

This half-way location is no coincidence: Alice Springs was originally simply a telegraph station, built precisely in the middle of nowhere for the Overland Telegraph Line, relaying messages between those coastal cities. Before the telegraph station appeared there was nothing there but a waterhole, that had been named by a government surveyor in honour of Alice Todd, wife of the Superintendent of Telegraphs, Sir Charles Todd.

When I visited the Red Centre it was baking hot, over 40 degrees Celsius, but without humidity, so it was surprisingly pleasant to cycle out to see the old telegraph station by the waterhole, a few miles from the modern town of Alice Springs, or just ’Alice’, as she is affectionately known by the locals.

Alice Springs is a small town but at the same time the capital city of Australia’s ‘outback’. It has a hospital serving an area of 1.6 million square kilometres, which is about one fifth of Australia’s gigantic land mass. Alice is also the base for the famous Royal Flying Doctor Service. Created by a combination of necessity and ingenuity in 1928, the RFDS pioneered the use of aeroplanes to fly doctors out to medical emergencies in remote settlements. I remember being mesmerised by the dramatic TV series ‘The Flying Doctor’ when I was a boy, thrilled by the heroic stories of lifesaving adventures in each weekly episode.

I had also heard about the School of the Air, the radio-based education service for children living in remote farms all over the outback, too far away to travel to regular schools, which is also based in Alice Springs.

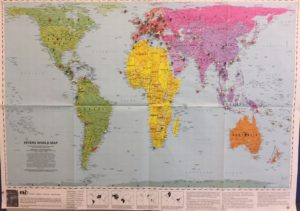

From Alice, it’s only a stone’s throw to drive out to Uluru. Well, that’s how it looks at first glance, showing them only a couple of millimetres apart, rubbing shoulders in the middle of the map. Then I realised that the distance between them is actually 467km, almost 300 miles; and again the sheer scale of Australia struck me. That’s something like the journey from London to Newcastle upon Tyne, or not far short of a drive across the island of Ireland, from top to bottom. We all know that Australia is huge and we’ve seen the image of tiny Great Britain superimposed onto Australia. But even when we know this intellectually, it’s a different thing to experience it directly. (The colossal distances first hit me as I flew into Australia from the north, when the pilot eventually announced we had crossed the coastline and then said that it would still be some hours before landing in Sydney, on my way to Melbourne.)

As we drove along the highway towards Uluru there was virtually no traffic. Every hour or so we might see another vehicle. This was so rare that drivers would acknowledge each other with a wave, as one might wave to a friend when driving in a town. Despite the lack of traffic I kept my eyes peeled, watching the road and glancing across the desert to the left and right. I had hoped to see kangaroos bouncing across the road at some point but we never saw any.

In the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, tourists were walking up the curved mountain-sized lump of orange stone that was named by Europeans as “Ayer’s Rock”. But Uluru, to call it by its proper name, has been a sacred site to the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people for thousands of years. My instinct as a mountaineer was to climb it but that urge was over-ridden by my respect for the indigenous culture and the wishes of the local people. In the end I just admired its beauty from down on the desert ground, watching a single line of people ascend slowly, plodding along in the heat like mindless worker ants.

Before returning to Alice we took our jeep off the main road, and drove deep into the desert, to experience camping in the outback. At night, the magnificent southern sky displayed a different part of the universe than we might occasionally see on a clear night in the northern hemisphere. With no ambient light, the darkness was absolute. The silence was terrifying. It was both intensely thrilling and deeply frightening to be so far away from civilisation, with all its safety and comforts we take for granted, and to be alone between the land and the sky. Out here, a snakebite, or even a broken down vehicle, could mean death.

Back in Alice, I had now experienced the Australian outback for myself, and had started to comprehend the endless distances between points on a map. Of course I was awe struck by its natural beauty, but I was even more moved by the human solidarity in its empty outback. Now I understood more directly the crucial importance of community in this vast space. It is from this harsh human reality that the Royal Flying Doctor Service was created and from the needs of isolated children that innovative radio-based education was invented. This is a community of people who might never meet each other, who hardly know one other, yet are bonded more strongly than urban neighbours because of their remoteness, their vulnerability and their absolute dependence on each other.

I found it intensely moving to think about the unspoken solidarity of this dispersed community and the loyal comradeship between people separated by geography, but bonded by humanity.

All this was on my mind when I went to the School of the Air and I watched a teacher, alone in a radio studio, conducting a lesson, teaching a class of children, without any of them able to see each other. Perhaps that’s why, in the centre of Alice, in the middle of Australia, watching the teacher speak into the microphone to invisible classmates, I had a lump in my throat and a tear in my eye.

Copyright © David Parrish 2018.

First published 20 December 2018.

Read more travel blogs and David’s travelling lifestyle business.

“Tourists don’t know where they’ve been, travelers don’t know where they’re going.”

Paul Theroux

Read more travel quotes.